Women of Atelier 17

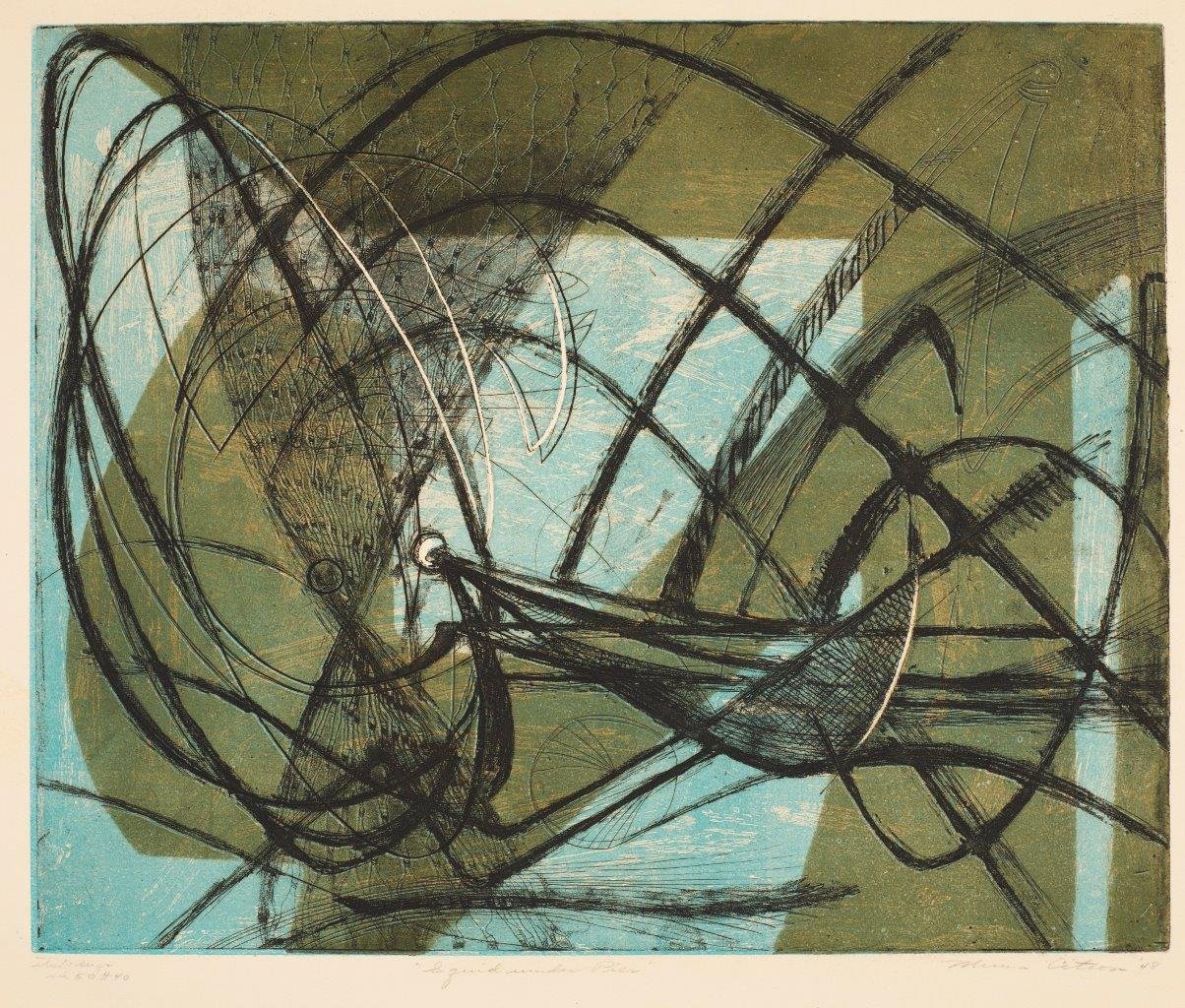

The Indianapolis Museum of Art’s newest print exhibition, Women of Atelier 17, opens with a large color print called Squid Under Pier by Minna Citron. The title is instinctively funny (perhaps the only cephalopod reference in the museum’s collection), and the energetic swirls and twists in the image are visually enticing. This great title and composition are the result of Citron’s own personal and artistic transformation, which can tell us a lot about the experimental printmaking that was happening within the New York printmaking workshop named Atelier 17.

Atelier 17 was founded by the artist and scientist Stanley William Hayter in Paris in 1927, and the name was drawn from the workshop’s street address of 17 rue Campagne-Première. He had intended the studio to be a space for experimenting with printmaking, especially with engraving and etching. Important Surrealist artists visited the studio, and Hayter fostered a collaborative environment where artists could learn from each other.

When World War II forced him to relocate the workshop to New York, Atelier 17 became a place where upcoming American artists mingled with French expatriates and experimentation opened the archaic-feeling world of printmaking to the values of modernism. It was also a place that, for the time, was unusually welcoming to women and their creative contributions. Citron was one of nearly one hundred women who seem to have been affiliated with the New York Atelier 17 during its 1940-1955 existence, eight of which are featured in the current exhibition.

Before Citron’s 1946 introduction to Atelier 17, at the age of fifty, she had developed a reputation as an urban realist, where her more traditional black and white prints of everyday urban life offered social commentary. One is included in the exhibition. Her experiences with expressive prints at Atelier 17 marked a dramatic transition in her work. As she put it, “I saw the students at Atelier 17 work with color and I also wanted to do color work thereafter.”

She also switched to abstraction. This enormous change seems to be rooted in not just the influence of the Atelier but also Citron’s hard-fought personal independence. She had felt smothered in her traditional 1917 marriage and began psychoanalysis in the mid-1920s to achieve “more personal freedom.” She and her husband eventually finalized a divorce in 1936.

Citron believed that great art could be personal to the artist while still having something to say to the unconsciousness of the general viewer—a very midcentury way of thinking. Adding this to the knowledge of her personal history and interest in psychoanalysis helps us read Squid Under Pier as a deeply personal image. When she exhibited this image in 1950, she wrote for the exhibition brochure:

The composition in “Squid under Pier,” which, some time [sic] after completion of the print, came to be called “squid,” is a threatening entanglement of tortuous, menacing lines: black lines, white lines, bitten lines and incised lines, with exciting variety in third dimensionality, forming a linear pattern of dynamic tensions and of great plastic depth. Contrasting with this disturbing agitation are the quiet interpenetrating, transparent planes of the neutral-colored “pier” and the fluid open areas of light-blue [sic] “sea” and “sky.” It is as though one might escape from these encircling tentacles to a temporary shelter and security under the “pier” and finally to peace and tranquility in the timeless and limitless space of fair skies and open sea.

The concepts of “entanglement,” “shelter,” and “escape” seemingly stand for Citron’s own personal journey. In her marriage she had felt entangled by the societal expectations for a twentieth-century wife, as well as by her own mother, who lived with the family, and her mother-in-law, who strongly influenced her husband. Some of the “menacing lines” were made by a printmaking process called soft-ground etching, which uses fabrics or other materials to create texture and pattern in a print. Citron used what looks like a twisted piece of a birdcage veil to create the netted lines in the center of the print, and it has been hypothesized that this could refer to those women. For more on how soft-ground etching worked, a video is on view in the gallery.

Although each woman at Atelier 17 brought her own artistic and personal background to her printmaking, and continued outward from the workshop in different ways, many shared Citron’s modernist interests in color, expressive abstraction, psychology, and experimental techniques. These themes repeat throughout the exhibition to tell a story of achievements by women artists during an era that overlooked them.

Women of Atelier 17 is on view in Golden Gallery until August 6. Its prints come from the IMA’s collection, but its research owes much to the book The Women of Atelier 17 by Christina Weyl, currently for sale in the Museum & Garden Shop. Squid Under Pier graces the book’s cover and is also a feature on the IMA’s self-guided tour for Women’s History Month.

Image Credits:

Installation view of Women of Atelier 17 in the Susan and Charles Golden Gallery, February 24, 2023–August, 6, 2023. Artworks © their respective creators.

Minna Citron (American, 1896–1991), Squid under Pier, 1948, soft ground etching and engraving, 14-3/4 × 18 in. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift of Dr. Steven Conant in honor of Mrs. H. L. Conant and Miss Joan D. Weisenberger, 1992.191 © 2023 Estate of Minna Citron / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.