Käthe Kollwitz: Art and Advocacy in Turbulent Times

Ever timely, Käthe Kollwitz’s prints continue to highlight the interaction between art and advocacy in unpredictable periods, more than a century after many were created. Born Käthe Schmidt in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia) in 1867, the artist came of age in the social landscape of the late Industrial Revolution, when the plight of the laborer was both at the forefront of public discourse but also ignored in favor of economic progress. Käthe inherited a concern for the living conditions of the working class from her politically minded family members, and this awareness grew into a lifelong subject in her artwork. As an adult, she experienced World Wars I and II, and between these events, she lived to see an enormous reconfiguration of Europe’s political and cultural boundaries.

Similarly, her career as an artist straddled between past and present, traditional and innovative. Her family recognized her skills early on, and as a young adult, she studied with artists in both Berlin and Munich. Though her training included a customary background in life drawing and painting, she would primarily use her skills for printmaking, a more democratic medium that could be seen by many and easily adapted to political publications and posters.

After permanently settling in Berlin with her husband in 1891, Käthe’s major break in the international art world came with the first of her historically inspired series, The Weavers’ Revolt (1893-1897). Based on a real uprising that took place in Silesia (located in present-day Poland) in 1844, Kollwitz was moved to depict the event after seeing a dramatization of the revolt, The Weavers, by Gerhard Hauptmann. The uprising was precipitated by lower payments given to the linen weavers of the region, who, post-industrialization, were now in competition with mechanization, and slowly slipping into poverty. Though the revolt was brutally repressed by the Prussian military, it was still viewed as a catalyzing moment for later workers’ movements.

Käthe Kollwitz (German, 1867–1945), Sturm (Attack), 1893-1897, printed 1921, ink on cream wove paper, etching, 9 × 11-3/4 in. (image). Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift of Joan and Walter Wolf, 2016.178.

Contemporaneous to Kollwitz’s own life, the same region once again experienced hardship in the early 1890s, this time in the form of famine. Given this context, Kollwitz’s Weavers’ Revolt was considered a subversive critique of Prussian leadership, and Kaiser Wilhelm II personally refused to award Kollwitz a medal at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition of 1898. The series was not only politically attuned, but highly experimental. Kollwitz used various print media, both intaglio and planographic, within the same cycle, and prominently featured women and children at the center of her narrative (Image above, Attack).

Following the series, Kollwitz secured a teaching appointment at the Berlin Academy for Women Artists, where she taught drawing and etching. Academic education in the graphic arts was only beginning to take shape in the early twentieth century, and Kollwitz was at the forefront of this movement, teaching fellow women artists.

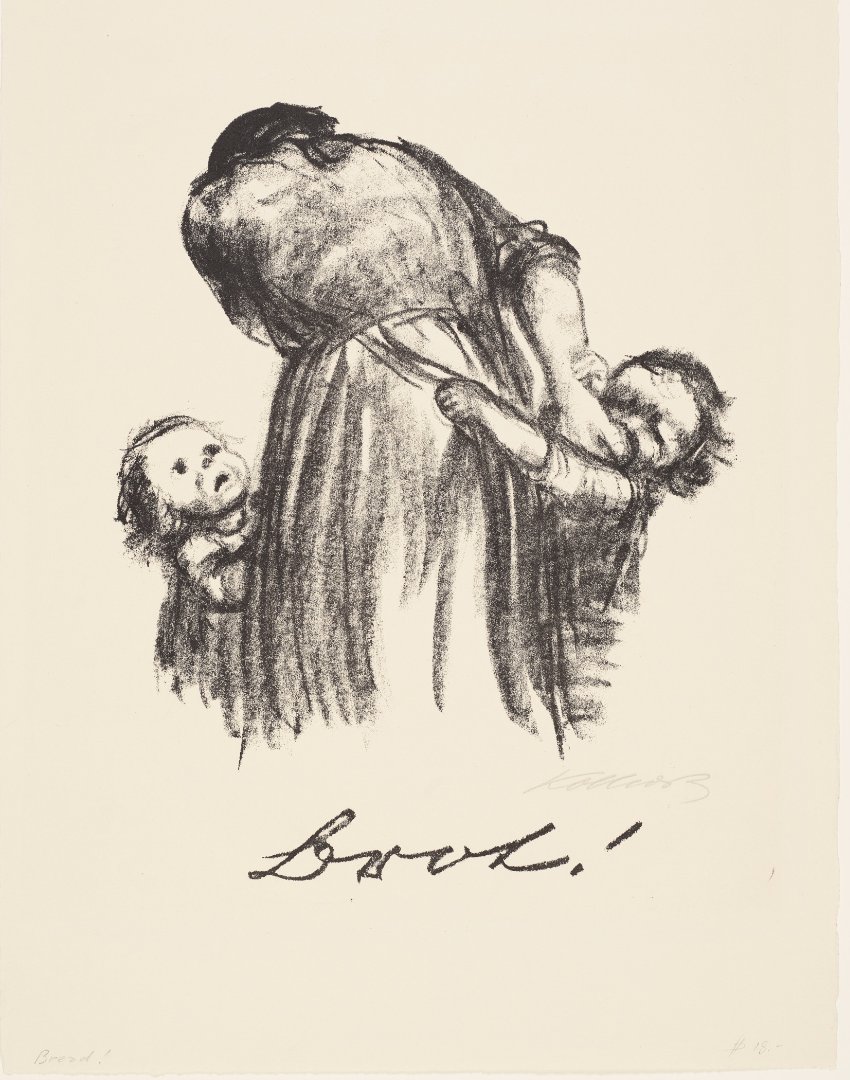

Käthe Kollwitz (German, 1867–1945), Brot! (Bread), 1924, ink on paper, lithograph, 21 × 15 in. (sheet). Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Julius F. Pratt Fund, 38.92.

World War I led to a marked shift in Kollwitz’s work, both in terms of subject matter and media. Now favoring woodcuts and lithography over intaglio methods, Kollwitz more directly engaged with the events, political discourse, and working-class hardships of her present. Lithographs, such as Bread!, created for an International Workers’ Aid campaign, brought awareness to famine in neighboring countries by depicting a mother faced with prioritizing which of her children to feed.

World War I also greatly impacted Kollwitz’s personal life. In 1914, the artist’s younger son, Peter, died while fighting in Belgium. Though Kollwitz had long depicted themes of maternal grief after witnessing her mother’s struggle following the death of her son, Benjamin. These images became imbued with new emotional force after the artist experienced the loss of a child firsthand. Many of her earlier prints portraying this grief, such as Mother with Dead Child, continued to be printed in new editions following the war. Additionally, her 1922-1923 woodcut series, War, which included multiple images of mothers, parents, and widows in mourning, crystallized her antiwar sentiments in print.

Käthe Kollwitz (German, 1867–1945), Woman and Dead Child (Frau mit Totem Kind), 1903, printed 1918, etching, soft-ground etching and drypoint, 16 × 18-5/8 in. (image). Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift of Brenda Kolker, 1991.274.

Despite her personal grief, Kollwitz achieved great professional success during the interwar period. In 1919, she became the first woman to be elected as a member and appointed honorary professor at the Prussian Academy of Arts. In 1928, she was given directorship of a masterclass in graphic arts at the same academy, a role in which she more directly influenced the next generation of print artists.

With the rise of National Socialism, however, Kollwitz’s political leanings did not go unnoticed, and she was forced to resign from the Academy in 1933. Her artistic output was further stifled when in 1941, her publisher, Alexander von der Becke, was forced to close his business by the Gestapo. Kollwitz continued to live in Berlin until 1945, when Allied air raids forced her to leave the city. She died just sixteen days before the end of the war while living near Dresden.

As an internationally recognized artist, however, her work was not diminished by the war and once again surged in popularity during its aftermath. Her publisher, who resumed work in 1946, still possessed thirty of her original plates, and his business continued issuing new editions into the 1970s, solidifying Kollwitz’s legacy as an artist.

Käthe Kollwitz: Visions of Solidarity and Resilience will be on display in the Charles and Susan Golden Galleries in the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields through August 3, 2025.

Recommended Reading:

Starr Figura, ed. Käthe Kollwitz: A Retrospective. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2024.

Käthe Kollwitz. The Diary and Letters of Kaethe Kollwitz. Edited by Hans Kollwitz. Northwestern University Press, 1989.

Louis Marchesano, ed. Käthe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics. Getty Research Institute, 2020.

Henriette Kets de Vries et al. Käthe Kollwitz and the Women of War: Femininity, Identity, and Art in Germany during World Wars I and II. Davis Museum at Wellesley College; Yale University Press, 2016.

Image Credits:

Käthe Kollwitz: Visions of Solidarity and Resilience in the Susan and Charles Golden Gallery, February 21, 2025–August 3, 2025.